In a world of clickbait headlines and 24-hour news cycles, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the constant stream of health advice. One week, coffee is good for you; the next, it’s not. A new study says walking isn’t enough. Then it is. So how do we make sense of it all?

Understanding the basics of scientific research can help you avoid being misled by sensational reporting and make more informed choices about your health.

Not All Studies Are Created Equal

There are different types of research, each offering varying degrees of certainty:

– Observational studies watch trends over time but cannot prove cause and effect.

– Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involve carefully designed comparisons and are considered the gold standard for establishing causality.

– Meta-analyses combine data from multiple studies and can offer stronger evidence — but only if the included studies are high quality.

Learning to distinguish between these is key. A headline based on a small observational study should be viewed very differently than a well-conducted RCT.

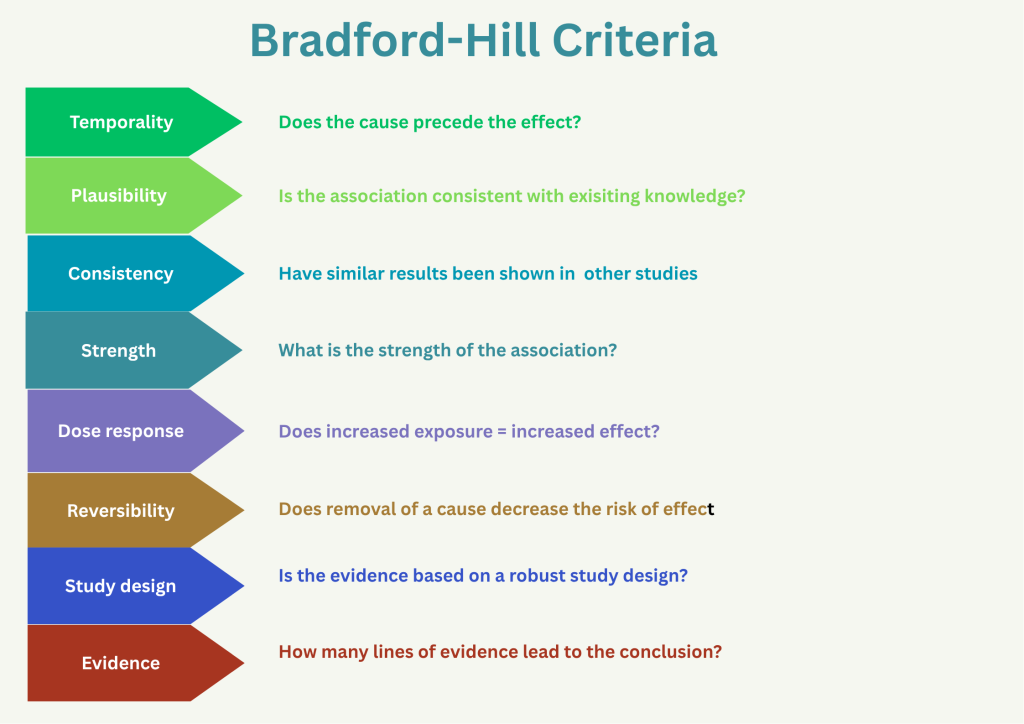

Understanding Causality: The Bradford Hill Criteria

To assess whether a relationship between two factors is likely to be causal, epidemiologists use the Bradford Hill criteria — a set of nine principles including strength, consistency, plausibility, and temporality (the cause must come before the effect). These don’t “prove” causation but help us think critically about whether one thing truly leads to another.

Relative vs Absolute Risk

News reports often cite relative risk, which can sound dramatic. “A 50% increase in risk” sounds alarming — but if the absolute risk goes from 2 in 1,000 to 3 in 1,000, the actual increase is quite small. Understanding absolute risk gives a more realistic view of what’s at stake.

Why Scepticism Matters

Even well-meaning scientists and reporters get it wrong sometimes. And even the best experts don’t have all the answers — no one does. Science is a process of discovery, not a collection of fixed truths. That’s why some healthy scepticism is essential. Ask: Who funded the study? Is it peer-reviewed? Does the conclusion match the data? Has it been replicated?

Who Can You Trust?

While no one is right all the time, some people consistently apply rigorous thinking and communicate complex science responsibly. Among those I trust:

– Dr. Peter Attia shares nuanced, in-depth interpretations of health research, often highlighting what we don’t know just as clearly as what we do.

– Chris Kresser provides a thoughtful, evidence-based approach that integrates ancestral health wisdom with modern science.

– Dr. Matthew Walker, a neuroscientist and sleep expert, communicates research in a way that’s both scientifically grounded and practical for everyday life.

– Dr. Andrew Huberman, a Stanford neuroscientist, is known for clearly explaining how lifestyle, behaviour, and neuroscience intersect. He also regularly distinguishes between strong evidence and early-stage findings.

All of them model the kind of thinking we need more of — careful, curious, and willing to change their minds.

Final Thought

When it comes to your health, resist the urge to follow headlines or trends blindly. Stay curious. Ask questions. Look beyond the surface. Trust the process of science, but don’t treat any single study — or expert — as the final word.